The Ginza hostess

For many years, I was hardly aware of the world of the Ginza hostess. But when I started walking through Ginza on my work breaks, a certain type of woman kept drawing my eye. It wasn’t because she was especially beautiful or well-dressed — there’s no shortage of such women to be seen in a central, upmarket district like Ginza.

And while she did have a certain sartorial style — wearing an elegant dress with a hem reaching to the ankle, mostly — that was not quite what set her apart either. Rather, in many cases, it was simply presence. It felt like I had just passed by someone who was, well, perhaps an actress or something.

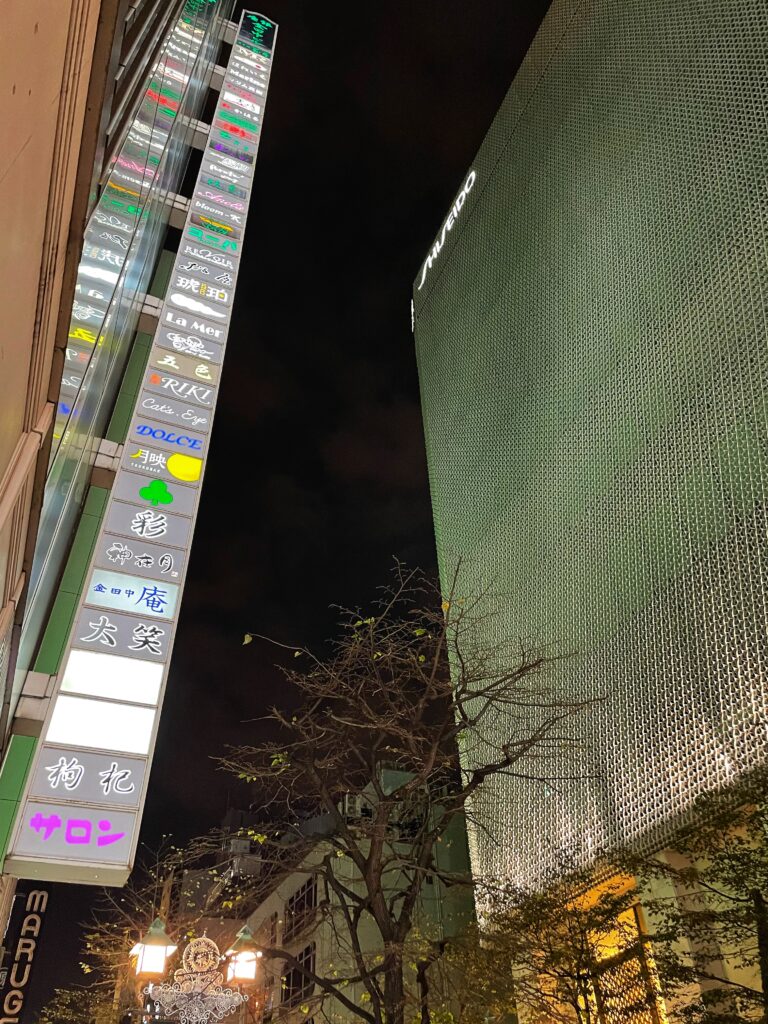

Then I would see this type of woman turn into a building beneath neon signs with the names of clubs (clubs named after flowers or the clubs’ “mama-san” owner/manager are quite common). When I had learned a little more about this world, I realised that while these women may not be actresses, they are accomplished performers, or entertainers if you like.

But what kind of performer, what kind of entertainer? What, since the long-past days of the Yoshiwara, has Japan’s modern incarnation of the courtesan become, in a society that is now so very different?

Since the frankly bawdy days described by Kafu in which the waitresses/hostesses of the Ginza cafes first emerged in the 1920s and 30s, one very important thing has changed in the world of the hostess today — not just in Ginza but wherever else hostess clubs are found in Japan (and there are many in every city and town, Ginza just being the apex).

While some men may still approach this world in search of sexual fulfillment, it no longer rests on the foundations of sex. And neither, for that matter, is romance, or romantic dreaming, a defining element, or at least not in the way it once was.

A man might expect to be flattered, have his jokes laughed at, be listened to, and made to feel good about himself, but will not, generally, be encouraged to feel that the hostess attentively refilling his glass and encouraging him to order more (with an eye on the bill) has become besotted with him or is sexually available.

If he does have hopes of developing a sexual relationship or finding love or at least a romantic adventure, he may succeed or may not, but the world has adapted to working without the promise of sex or romance.

It’s hardly surprising; when it comes to values around relationships, Japan is now much like any other modern, consumerist society, believing that romance, ideally anyway, should be found in freely chosen monogamous relationships, and that fidelity can’t just be for women.

But is a chance to blow off steam and enjoy a bit of flattery what the Ginza hostess club is charging such fantastic prices for?

Yes, and no.

Lending a sympathetic ear to a man, and making him feel that he has engaged the attention of a sexually desirable woman, is the most fundamental role of the hostess and perhaps her defining characteristic, and in this, the Ginza hostess is no exception. And, as has always been the case in the world of the Japanese courtesan, from the days of the Yoshiwara through the rise of the geisha, each hostess will have “her” customers and the customer will have “his” hostess.

But if one listens to what some of the mama-sans— the kimono-clad elder women (ex-hostesses themselves) who have traditionally owned the clubs — say publicly when they describe their world, then the Ginza club is offering much more than this, and in a way that sets it quite apart.

One of the most famous mama-sans in Ginza, who started her own hostess career in the district in the late 60s, describes her club in a way that makes it clear that what is chiefly being sold to its well-heeled customers is “success”— its recognition, its celebration, and, not least, its facilitation.

A true Ginza hostess, she says, does not flirt with her customers, or only in the lightest of ways; at any rate, she is not selling sex appeal. And neither will she engage in “idle chatter.” Instead, she entertains; and given the nature of the customer in a Ginza hostess club, that is something quite different. It means fluently managing conversations with figures at the top end of the worlds of business, arts and sports. And that requires, apart from a talent for witty repartee, knowledge.

The mama-san says that she herself, having left education after high school not knowing much about anything, went to great lengths to educate herself about a range of fields in order to succeed as a top hostess. Such women, then, may well start the day reading the Nikkei financial daily, or perusing arts magazines, or the sports pages, or all three.

The hostesses, though, while they may draw people to the clubs, are not in the end the entire point. The mama-san, rather, sees her club, and its elite customers, as a network there to be used — a place where leading people in a range of fields can meet each other and hear each other’s stories, and if all goes well, make connections and think of ideas that will help them achieve further success.

From this perspective, the hostesses are there to allow all this to happen by making the atmosphere sparkle. And in this manner, this mama-san, and others, see the Ginza hostess clubs as being, in effect, part of the functioning of the Japanese economy; oil — albeit very refined oil, of course — that eases the cogs.

And indeed the hostesses, part of whose job is sometimes to dine with clients before going to the club and go to karaoke or bars with them afterward, do sometimes sit in on informal business discussions.

Along with this enabling of success goes the celebration of it. The customer will be addressed with the most respectful language and, according to the mama-san, be “put on a pedestal.” And it is clear, too, that she and other mama-sans, who in many cases have come from relatively humble backgrounds, feel an affinity for their customers.

The mama-sans have, after all, trodden a path through hard work and ambition to the top of the Ginza club world. They are, in many ways, part of the elite world to which they cater.

Indeed, the elite nature of the Ginza club can’t be overstated. Customers can’t just turn up off the street — they need introductions. This is itself a kind of vetting procedure, but it goes further. Payments are generally not expected to be made on the club premises. Instead, a bill is sent addressed to the customer at his office — a way of ensuring he is who he says he is.

Another way of doing this is for a bowtie-wearing man (who otherwise serves drinks, accepts coats or parks cars for a club) to show up at a customer’s office with a small gift of thanks for his custom.

(If a customer isn’t who he claims to be and there is no one to pay the bill, the money then becomes owed by the man’s hostess to the club. But the risk to the hostess of such occurrences is offset by the amount she can earn from genuine well-healed customers).

It seems, then, looking at the club in this light, that the world of the contemporary “courtesan” couldn’t have evolved further from its original Yoshiwara exemplar. No longer in any way subversive, it supports the elite.

And indeed, since it no longer rests on the foundation of romance, let alone sex, could one even risk an apparently far-fetched comparison between a top Ginza hostess club and a London gentleman’s club? What the mama-san said about the purpose of her club could easily be applied to the London club, too.

But at the same time, the two environments couldn’t be more different. However one defines the alchemy by which the former works, the magic ingredient in the latter is simply the presence of beautiful women.

Indeed, while the mama-san cited above insists her club is a “wholesome” place — top hostesses don’t flirt, after all, or only in subtle, restrained ways — she tells a revealing story of a customer bringing his daughter along with him on one occasion.

A Ginza club, she says, ought to be the kind of place where this might happen. But the daughter, seeing her father become a different person once he crossed the threshold of the club, comments that she had never seen him smiling in such a fulsome way. A Ginza club must be like that, too, the mama-san says.

And such a man, she adds, is also her ideal customer — a man who is not a playboy but a family man who at the same time knows how to have fun.

It should be mentioned, too, that a customer does not choose his hostess, or she him. The pairing is made by the club’s mama-san and whoever made the introduction. It is meant to be a good fit, but it’s a pairing that cannot be altered so long as the customer goes to that club or the hostess works there.

At the same time, while the customer is wedded to his hostess, she will have more than one customer. This has given rise to the “help-san,” a kind of assistant hostess who sits with a customer when the hostess is busy with someone else.

Perhaps then, after all, there is something of the Yoshiwara about the modern Ginza club; the male visitor certainly engages with the beauty and charms of the female hostesses — what would be the point of it otherwise? — but in a spirit of play, which demands an ability to recognise the artifice but enjoy it anyway.

And the hostesses, the mama-san says, and she herself, too, are indeed like actresses — at the very least they must leave behind any personal troubles they have — for each night is a performance.

Another long-established mama-san in Ginza makes a similar point.

According to her, Ginza should be chic, its hostess clubs should be chic, and that means that people coming to them should be chic, too. But the word she uses that is usually translated as “chic” — iki — is an interesting one. Part of the way one shows iki, for instance, she says, is not letting on when things are down. Rather than anything sartorial — being well and expensively dressed — it’s a mental quality, an attitude to life that she means.

Iki is a term that first came into use in the early 18th century, in the first great flourishing of the Yoshiwara. It was used primarily of courtesans, and later geisha, but became a term that could be used more generally about people.

According to one scholar of the Edo period, it came to involve three elements — the forthrightness and eschewing of excessive social tact or adroitness called hari, which we have met before with the early courtesans, along with sexual allure and urbanity.

When it comes to sexual allure, though, like the Ginza hostess, it was meant to be at most a kind of light coquettishness, certainly not obvious or pronounced. And, more importantly, it was an allure that always had to remain a potential. It could never survive, for instance, real love, or a real relationship — it is a promise, beamed out from flashing eyes to all, that must remain forever unfulfilled.

Urbanity is the quality we met before in the ideal customer of the Yoshiwara — one who knows its ways, and knows what it is, who observes the Goldilocks rule of “not too hot and not too cold” (for instance, being neither too stingy nor too spendthrift with money), and who, in sum, can joyously embrace what it offers while fully aware of its artifices and pretence.

If one takes this attitude required of the ideal customer — the ability to shrug off troubles and treat what goes on in the club as a game that, despite the artifice, can be fully enjoyed by taking it both seriously and not seriously — and generalises it as an approach to life in general, then it becomes seductively attractive.

Indeed, it’s tempting to see the equanimity it implies and the “middle way” approach as having something in common with the Buddhist principles that underly elements of Japanese culture. And all this came directly out of the culture of the courtesans.

It was a thought, anyway, to take away with me as I passed by a hostess entering a club with some smartly dressed but much older man.

It no longer appeared to me, as someone from a culture without a courtesan tradition, that there was something wrong about the scene — about the fact that a man would pay for a woman to pour his drinks and show interest in everything he has to say; viewed from another angle, here was someone — I liked the think, at least — bobbing happily, or perhaps it would be better to say lightly, on the surface of Japan’s old “floating world.”

Ginza in decline?

Talking of Buddhism reminds me that nothing ever lasts; change is a law of the universe, and Ginza is no exception. The heyday of the hostess world, and the district itself, has long since floated past, and it’s now some way back in the river of time.

Few, probably, would argue that its greatest flourishing was in the 1980s during the height of the bubble economy when stock and real estate prices seemed to vault ever upwards — it is a world, after all, that is a plaything of the rich; the Yoshiwara, too, was at its most effervescent when underpinned by prodigious feats of spending by merchants.

The two mama-sans are both well aware of the district’s decline. It is not just that there is less money around than there once was — the surrounding culture is changing too. For one thing, they note, the importance of drinking together is lessening in the Japanese corporate world.

It’s also hard not to imagine that when Japan does finally move toward gender equality at the top of society, not least in the boardroom, the appeal of the Ginza clubs may begin to fade.

Meanwhile, the corporate world that the clubs serve is beginning to turn its own attention to the Ginza club scene, and the huge sums of money spent there. More and more of the clubs are coming under corporate management rather than being not just run but also owned by mama-sans with their decades of imbibing and imparting the Ginza spirit as former hostesses themselves.

The second mama-san has long run what is known as a bundan hostess club, meaning one that primarily attracts literary types, both writers and editors from publishing companies — their presence in Ginza is one of the legacies, in fact, of the Printemps age, and the makeup of the clientele at that cafe’s opening.

In fact, bundan clubs deserve a special mention, as they can act as a kind of gateway to the Ginza hostess to people in the literary world that is not available to others. Less expensive in general that regular high-end clubs (though not in any sense cheap), they charge different prices depending on age or the ability to pay. And then, once a person has “made it,” and got rich or famous or important and can afford a regular high-end Ginza club, the mama-san of the bundan will make an introduction.

However, the number of such clubs has dwindled in recent decades, she says. It appears, then, that having set the tone for Ginza for over a hundred years, the Printemps legacy may be fading at last.

All of which may be true…

Postscript

…but none of this has yet affected the district’s lively population of historic ghosts. I found a new one recently, in the north section of Ginza.

I knew from a biography of Soviet spy Richard Sorge, a German journalist who lived in Japan before and during World War II, that he used to frequent a German restaurant in Ginza — and there it was, modern-looking now, but still very much in existence.

Though Sorge was eventually unmasked by the Japanese authorities and executed, his contacts at the German embassy in Tokyo had allowed him to learn of Hitler’s plans for an invasion of the Soviet Union — intelligence that he passed on to a famously disbelieving Stalin.

Nevertheless, he was able later to inform the Soviets in 1941 that Japan, as it prepared to enter the war, had decided not to take on the then-beleaguered Soviets but to head into Indochina in a strategy that would bring it into conflict with the United States and the British Empire instead.

This time the Soviets listened, and were able to move units from the Far East to help the country survive the onslaught of Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa.

I’ve yet to find out whether the restaurant is at exactly the same location as the one Sorge visited, but, as I passed it by, it was nice to imagine Sorge sitting there over a plate of sausages, looking out over Ginza, perhaps hearing the chimes from the the Wako Ginza clock, and thinking about how he was about to tip the war significantly towards the eventual defeat of the Nazis.

Ginza district’s official tourist website

End