The Yoshiwara pleasure quarters

Like anywhere else in the world, Tokyo has always had prostitution. In fact, given that in its early days, men considerably outnumbered women, chiefly due to the system of requiring all daimyo feudal lords to maintain huge and costly establishments in the city with large retinues (of male samurai), it probably had more than its fair share.

But, unlike many other parts of the world, it has also had courtesans, which was something different. The practice was probably originally inspired by the Chinese example, and, when Edo was built, a quarter — walled and moated — was dedicated to them. Inside it, the “castle-topplers,” a Chinese-derived term alluding to how powerful, and potentially ruinous, an effect a top courtesan could have on even the most powerful of clients, were licensed (thus legal).

Outside, in the rest of the city, prostitutes ranging from relatively expensive “gold cats” and “silver cats” to less expensive “singing nuns,” “boat tarts” and “night hawks,” weren’t. However, it is only the courtesans who concern us.

You may have seen a picture of a courtesan of Edo already without knowing it. They were one of the main subjects of ukiyo-e prints, along with actors and sumo wrestlers and views of famous sites. Though courtesans were mostly confined to their quarter, called the Yoshiwara, the top ones became celebrities — the superstars of their day.

Particularly in the Yoshiwara’s early period, the women were highly accomplished practitioners of a range of arts and pastimes — a list might include the shamisen and flute, singing, tea ceremony, composing haiku, calligraphy, playing the games of go and backgammon, and even kickball. Unsurprisingly, visiting them could be extraordinarily expensive. A first visit, some have estimated, could cost upwards of $8,000 in today’s money for the most expensive courtesan, when including food and drink, money to pay musicians and other entertainers, along with tips to assorted Yoshiwara staff and hangers-on.

And not much would happen on a first visit other than a kind of ceremonial acceptance of the “suitor.” It was only after a third visit that a man might be expected to be received by the courtesan in the full sense.

Sex, though, was not what the quarter was selling, at least not primarily. That could be had much more cheaply in the arms of a “singing nun,” for instance, at any of the city’s many unlicensed brothels. Instead, according to Cecelia Segawa Seigle, author of the excellent “Yoshiwara”, the quarter, a place mostly reached by boat up the Sumida, was more like an elaborate stage on which to create the illusion of romance, to offer — to those who could afford it — the feeling that a woman of remarkable beauty, presence and accomplishments was very much taken with you, and perhaps even in love.

Courtesans, in short, encouraged customers to give full vent to romantic feelings that were not then expected or supposed to exist with any regularity within marriages. As Seigle noted, if the courtesan wished to appear in love, she had an array of tricks. To produce wet eyes on parting, she might pull an eyelash, or stare very hard at something very small without blinking, or rub her eyes on a sleeve lined with a bit of alum beforehand (and that was supposed to be good for the eyes, too!).

The clients, meanwhile, were expected to remain faithful to their selected courtesan — or certainly not to start wooing a courtesan from a rival house. On the other hand, very occasionally, some courtesans did fall in love. Ironically, since this was when real feelings overflowed the boundaries of the quarter’s deliberate theatricality, such relationships with clients, usually doomed to end badly, were a popular dramatic theme for the real theatre.

The quarter’s recreation of reality went deeper than just pretend love, though. In fact, within its moat and walls, it subverted the class structure, one that exalted the warrior above all others. Visitors were required to surrender their swords on entry — the long and short sword of the daimyo and samurai, and the single short sword that a few of the more important townsmen were allowed to wear, thus removing one of the most obvious class markers.

And while laws meant to keep the merchants in their place limited their spending in ordinary life, once inside the quarter, they could rival daimyo for the affections of courtesans through the sheer power of their money. And let’s not forget the courtesans themselves — while reigning over the quarter and its male suitors as the objects of desire in the pretend world of love, they belonged to the lowest level of the official class system along with other entertainers including kabuki actors.

The theatricality of the Yoshiwara extended to public show as well, with events that drew crowds of townspeople who could never have paid the price of a courtesan themselves. One of the most remarkable performances was how a top courtesan would walk — if that is still the right word — down a Yoshiwara street to meet a client.

In an extraordinarily choreographed exercise, the courtesan would turn each step into a stylized backwards-and-forwards figure-of-eight movement with the foot. As a result, though the distance traveled was no more than a hundred yards or so, it could take considerable time.

It’s hard not to draw a parallel with the stylized movements of kabuki, and the parade seems to show yet another way in which the two worlds mirrored and fed off each other. In the early days, before a courtesan’s dress became excessively ornate, the courtesan would show a naked foot and ankle, lightly whitened with powder, as she swept up the hem of her kimono.

It was, no doubt, somewhat titillating. But the main draw must have simply been the sheer sexual charisma of the woman as she stamped her presence in the minds of onlookers with each step — a modern comparison might be a supermodel on a catwalk. And then there was the kimono the courtesan wore, for, in the quarter’s heyday, the courtesans were trendsetters in style for the city’s women, too.

Talking of the woman’s charisma, there was a word, in effect, for this: hari. It’s an old Japanese term no longer in use, but it appears to refer to a combination of boldness and forthrightness and independence of spirit that at the same time had an element of what was seen as pure-heartedness to it.

Aside from personal demeanor, this could be shown, for instance, by a courtesan who for some reason rejected an aristocratic suitor, or showed contempt for a merchant’s money when he had strayed into crudeness in throwing it around. Such as act would instantly win the hearts of the general populace.

So much for the quarter’s women. But what about the men who went there?

As part of its subversion of class distinctions, the world of the courtesan helped give rise to values and sensibilities that stood in stark contrast to the Confucian ethic behind the warrior class’s supremacy. Indeed, as Seigle notes, the samurai, who were supposed to uphold the values of frugality and self-denying service, were at something of a disadvantage within its walls; they were in danger of appearing as boors who “just didn’t get it.”

In contrast, familiarity with the ways of the quarter, and its conventions and protocols, became the mark of the urban sophisticate. Consider the play-acting around romance. Those who “got it” were not taken in. Understanding, accepting, and indeed delighting in the fact that the whole thing was a performance was supposed to mark the height of sophistication. It was only boors who took it too seriously, or, even if they understood its real nature, didn’t have the wit and grace to play the game properly.

And one could fail in so many ways — being too stiff (likely to be a samurai) or gullible (a samurai up from the country on his first visit), for instance. For a wealthy merchant, it might have been straying across the fine line that existed between frittering away money with heroic abandonment and, as mentioned above, simply being too crude in the way one vaunted one’s wealth.

With these essentials of Japan’s traditional courtesan culture in mind, we can now return to the Ginza and its mushrooming, waitress-filled cafes.

The Ginza of the cafe waitresses

By the time the waitresses began to emerge in Ginza, the age of the Yoshiwara courtesan was long over. The quarter, though it continued to exist right up to the aftermath of World War II, had gone into precipitous decline in the 19th century and ended up being little more than a licensed red-light district. Into the void had stepped geisha, who first emerged in the quarter as entertainers (their name literally means a “person who performs” or “person of art”). By the dawn of the Meiji era, they had already wholly supplanted the women of the Yoshiwara as the companions of rich and powerful men, a role they would keep right up to the end of the war.

Today, the number of geisha is very small, and they are largely associated with Kyoto, in keeping with their reputation as vessels of traditional Japanese culture, trained in dance and music and old-fashioned “party games” far removed from contemporary life. But their numbers were once considerably larger, with several prominent geisha quarters in Tokyo, and, with both “high” and “low” class geisha, the image of the women was more varied.

Two books by Nagai Kafu, the great chronicler of Tokyo’s demimonde, capture the world of their heyday, and then the way the world of the hostess grew up alongside it, just as geisha had themselves originally emerged in the world of the courtesan. The first book, “Geisha in Rivalry” (in another translation “Rivalry: A Geisha’s Tale”), was published in 1918 but covers more or less the period when the Printemps and Paulista opened.

In this novel, the demimonde belongs to the geisha and geisha alone, and the main setting of the story is to the immediate south of Ginza in the Shimbashi geisha district, a world that, in cultural terms, was wholly Japanese. Ginza gets no mention while the Yoshiwara itself is just a place where a penniless and dissolute author has spent a couple of debauched nights.

The geisha we meet include those who are indeed highly trained and accomplished performers in traditional music and dance, and also those who have drifted into the role with other, rather less artistic, talents, in a prewar world in which men were still licensed by society to roam outside of marriage in pursuit of mistresses or sexual or romantic adventure.

But by the time Kafu had penned the novella “During the Rains” in 1931, the scene had shifted to Ginza.

Here’s how he describes a cafe near the start of the tale: “A pair of nude plaster women, one on each side of a wide archway in a twenty-five-foot facade, supported a sign in roman letters that read ‘Don Juan’.”

The customers enter through a “big stained-glass door” to a space “cluttered with tables and chairs set up in booths on both sides of single-leaved screens” and with a bar stocked with foreign liquor. From the ceiling, “artificial flowers twined around paper lanterns” while beside the many potted plants, there was a dense stand of shrubbery that made it look as if a “stage bamboo thicket had been installed.” Upstairs was a room with mirrored dressing stands lining all four walls for the waitresses to prepare.

In form or outward appearance at least, it was a wholly new world.

Once they had arrived in Ginza, the cafes became the hardiest of plants in its soil. Consider the 1923 earthquake. In its aftermath, so-called “barracks cafes” were immediately thrown up with any materials at hand on whatever patch of ground was available (without bothering with foundations).

Some of them were even decorated by artists’ collectives to brighten up what was otherwise a scene of devastation. Indeed, by 1929, official data records some 600 cafes in Ginza, according to Edward Seidensticker, author of “Tokyo Rising,” still the classic history of Tokyo along with its prequel “High City, Low City: Tokyo From Edo to the Earthquake.” And they were attracting fashionable crowds.

The word “ginbura,” which refers to wandering around in the district in something like the manner of the Parisian flaneur, first emerged within just a few years of the opening of the Printemps and Paulista and became a catchword of the liberal Taisho era (1912-1926) and the first few years of the following Showa era.

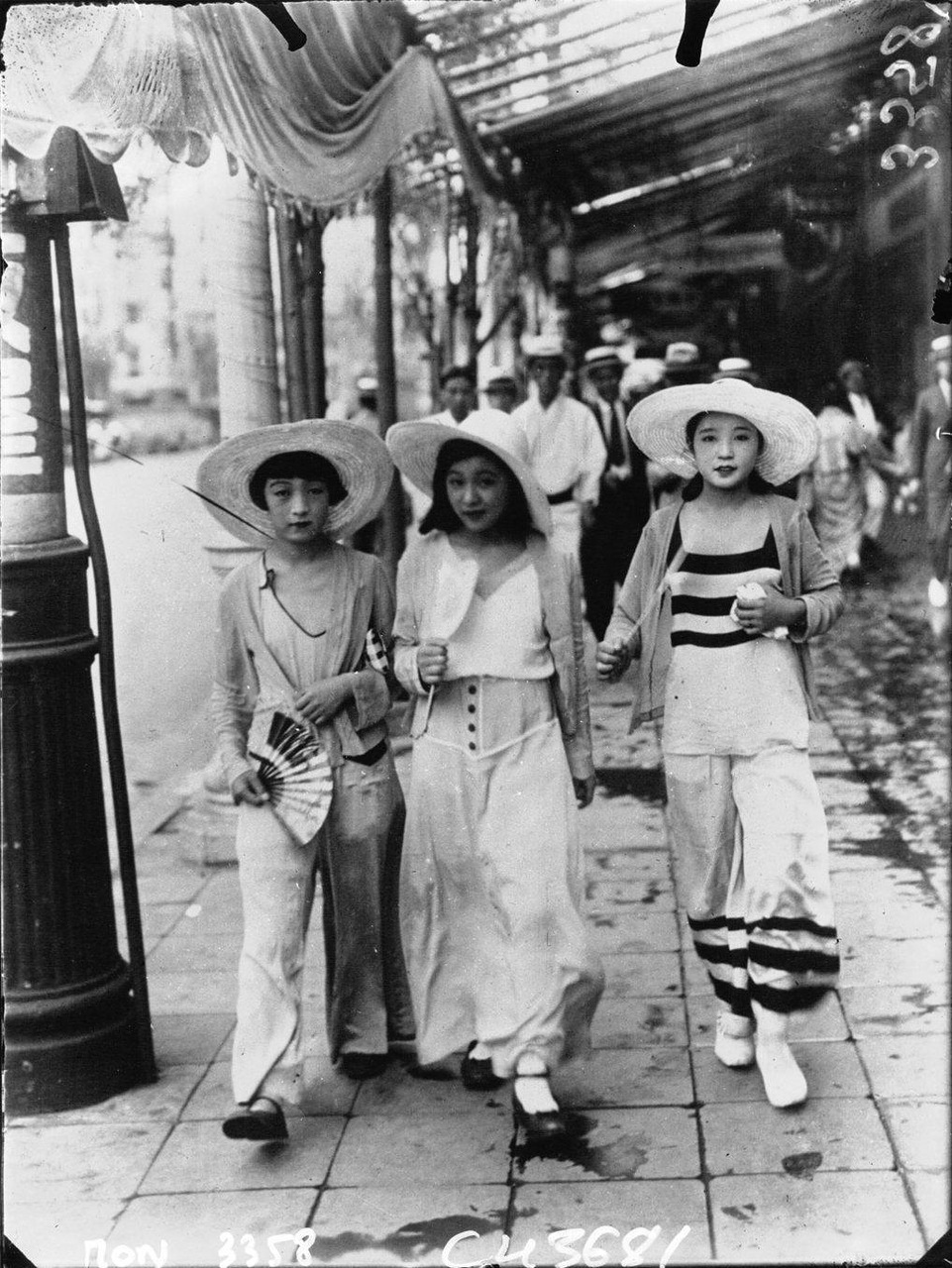

It typically referred to “moga” (modern girls) and “mobo” (modern boys), who adopted Western 1920s fashions and consumerism (and with plenty of attitude, with the women shocking the older generations by being as likely as their male companions to be found with a cigarette dangling out their mouth and a stiff drink at the ready.)

And the sorts of people who had made up the original Printemps crowd — painters, novelists, artists and the like — had made Ginza one of their main haunts, a legacy that today is perhaps most obvious in the number of art galleries concentrated in the district.

But we have to distinguish now between two types of “cafe.” Some were spiritual descendants of the Paulista rather than the Printemps, meaning that the coffee took precedence — they were early versions of what are now called kissaten, individually run local cafes that have become something of a Japanese urban institution, though sadly now in decline. But in Kafu’s fictional Don Juan, we see the Printemps-style cafe well on its way to evolving into the modern hostess club.

And there were plenty of them. As the waitress Kimie, the main character in “After the Rains,” arrives for work and looks down the street, she sees “as far as the eye could reach, almost side by side, the same sort of cafes.” It would have been easy, Kafu tells us, for her to enter the wrong one by mistake. But they were also becoming expensive. An ordinary salaryman, for instance, would probably not be able to afford more than one visit a month, according to Seidensticker.

So what was the relationship, then, between this world and Shimbashi’s geisha district just to the south? In “After the Rains,” some of the waitresses of the Don Juan moved back and forwards between that role and being geisha themselves, but at the lower end of that latter profession, lacking most of the artistic accomplishments associated with geisha today. It was more or less the same type of calling but just in different costumes and in different settings.

The world of the geisha, however, both high and low, would shrink dramatically in the Japan that emerged from the ashes of WWII. The Shimbashi geisha district, for instance, has now vanished. In part, this is because time simply stopped in the geisha world, which preserves a style of entertainment now a century or more old.

In contrast, the Ginza waitresses would embrace the future; places like the fictional Don Juan began a sharp upward rise after the war in both price and exclusiveness as the Ginza waitress evolved into the modern Ginza hostess.

Continued…