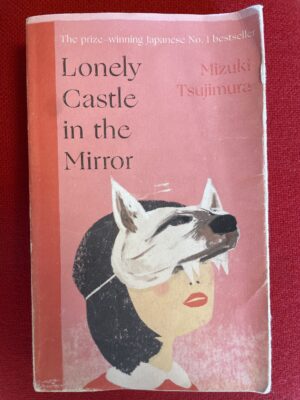

Mizuki Tsujimura’s Lonely Castle in the Mirror

A review

If one wanted to point to some social issues particularly affecting Japan, at least as the country itself sees it, bullying might come to mind — bullying in schools primarily, though also more generally in society, including in the workplace.

Perhaps there’s even something inevitable about the phenomenon in Japan, if one views it as the flip side of the pressure toward social conformity. To be different, to stand out, or to stand out too much, at any rate, is sometimes to invite trouble. Another, related issue is kids refusing to attend school — often, but not always, because of bullying.

Some progress has been made with both issues in recent years. Legislation enacted in 2013 on reporting bullying, for instance, has sought to shine a spotlight on the phenomenon and break down a wall of silence and denial that Japanese schools and local education authorities have sometimes tried to erect around it.

The result has been rises in cases — recorded cases that is — which is a good thing if it means that school bullies are operating undetected less often. Meanwhile, so-called “free schools,” which, while not accredited by the government, aim to offer a safer environment to vulnerable kids, have mushroomed. Their rise has been accompanied by an increase in school absenteeism (from accredited schools, that is) to record levels in recent years.

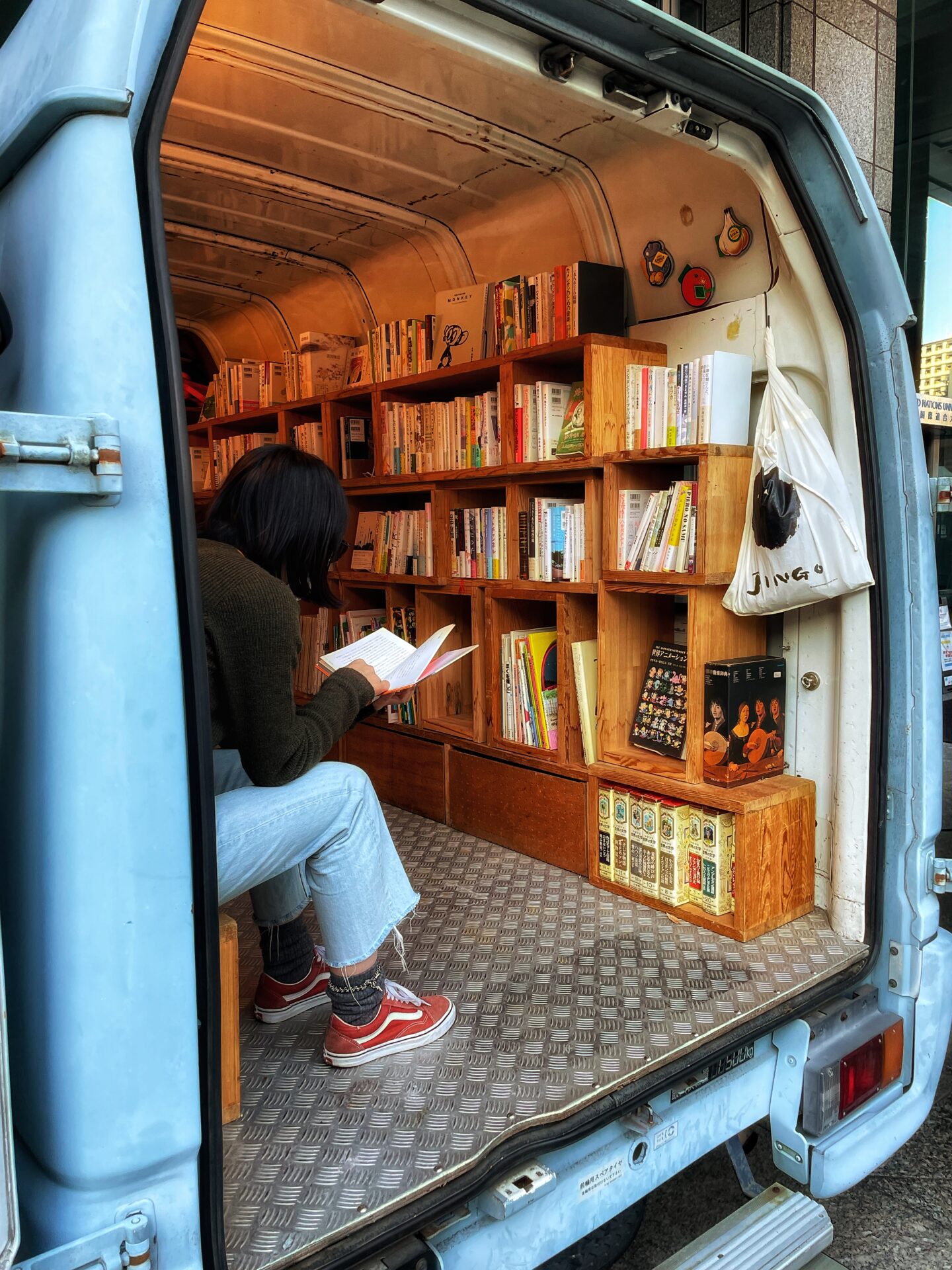

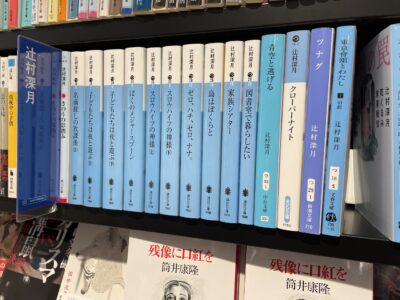

Mizuki Tsujimura’s novel Lonely Castle in the Mirror, which has sold half a million copies in Japan since its publication of 2018, is about seven kids who have stopped attending school for a variety of reasons, but mostly because of how other kids have treated them. One day, the mirrors in their bedrooms (for most of them) start shining, drawing them in. On the other side is the mysterious castle of the book’s title.

The Japanese term for “lonely castle,” 孤城 (kojou), could also have been translated as “isolated” or “solitary” castle. The kids are certainly lonely, but perhaps the word “isolated” would get closer to the heart of their problems. Bullying, at least as outsiders would view it (though not all of the seven kids wish to acknowledge they were victims), is why most of them have stopped attending school, but that’s not what Tsujimura focuses on — or at least not with anything like the visceral intensity that Mieko Kawakami does, for instance, in her recent novel Heaven.

Instead, Tsujimura shines a spotlight on the state of being cut off from contact with others — the seven kids are all isolated to a degree, and in the case of Kokoro Anzai, the 12-year-old girl whose perspective dominates the book, perilously close to hikikomori, or total social withdrawal, a phenomenon especially prevalent in Japan.

The experiences the seven kids have had feel like they cover most of the typical paths that lead from the classroom to shut-up in the bedroom, although some of them do have a particularly Japanese flavour. Being shunned because of standing out for an unusual level of talent, for instance (for the piano), is one; another is Kokoro’s inability to reach out to her mother, despite the mother’s obvious sympathy and desire to understand.

Foreign readers of Lonely Castle in the Mirror should know that Japanese culture does not highly value speaking out about one’s feelings, and bear in mind, too, that the general cultural inclination in Japan toward endurance, or gaman, when things are tough — a trait that won the Japanese a lot of praise from foreign observers for their dignified behaviour in the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake-tsunami and nuclear disasters — can also become the clay from which bricks of isolation are formed.

The novel at first appears to put Kokoro and the other kids in a conventional fantasy adventure (Young Adult fare, in fact, of the sort that might appeal to the book’s seven kids). A mysterious girl in a wolf mask greets them as they arrive through their respective mirrors and tells them that the castle will be open for a year or so and that it contains a key to a wishing room. Whoever finds the key, and the room, will have a wish come true.

There are some other rules, adding some complications and dangers: if someone does succeed in making a wish, the castle will disappear and everyone will forget ever having been there; and the castle is only open during the day (in other words, it’s only for those not attending school) — if anyone stays beyond its 5 p.m. closing time, they will be eaten by a wolf (whose howls can be heard as closing time approaches).

The plot expectations Tsujimura sets up, though, are quickly subverted. Partly, this is a matter of the castle itself. It is a very strange place, but not in a fantastical sense — it appears unreal, odd, off somehow, even within what had initially appeared to be the book’s fantasy genre setting.

Among its strange quirks are the presence of baths but no toilets, no water from the taps, no food in the kitchens’ vast empty refrigerators or even gas to cook with, and very little sense of where it might exist — i.e. of anything outside it (windows are frosted, except for glass doors with a view of a courtyard, though there’s no handle to the door so any chance of going out into it). Why exactly does the castle exist, and where is it?

If this suggests that rather than a tale of adventure — fantasy or otherwise — the book is a mystery, then yes, in form, at least, it is, and works well as one (while some readers may in fact piece together some of the castle’s secrets before they are revealed, few are likely to be disappointed with how well it all fits together).

Nevertheless, Tsujimura’s true purpose for the kids is for them to find ways to solve or unlock the sense of isolation that they feel — and perhaps even to reach their fictional hands out in encouragement to actual young readers out there stuck in their own isolated realities.

In fact, the way that Lonely Castle in the Mirror, ostensibly a work of YA fiction and written in very plain language, operates on several levels at once is surely one of the reasons that it has appealed so strongly to maturer readers, too. Kokoro’s mindset, for instance, guides the pace of the novel.

As some readers have noted, sometimes critically, the pace is slow at first, but this can be seen as reflecting the fact that for Kokoro, to begin with, the mysteries of the castle, and the prospect of finding the key, are nothing compared with the puzzle of understanding the other kids; we move forward at the pace of her ever-so-hesitant steps as she initially obsesses over the smallest signals of the others’ feelings. As she warms up, the plot hots up, and in the second half moves quickly to its very emotionally satisfying conclusion.

The castle itself, meanwhile, is a multifaceted metaphor for spaces of refuge and healing. Its meanings surely include fiction itself, while the castle’s rules regarding wishing and memory (the question of how much it matters if all the positive experiences gained in the castle are forgotten is pored over by Kokoro and the others) appear to suggest that the ultimate goal for such kids is that they should come to forget — no longer feel reliant on, that is — whatever role sympathetic outsiders may have played in their recovery.

Continued…